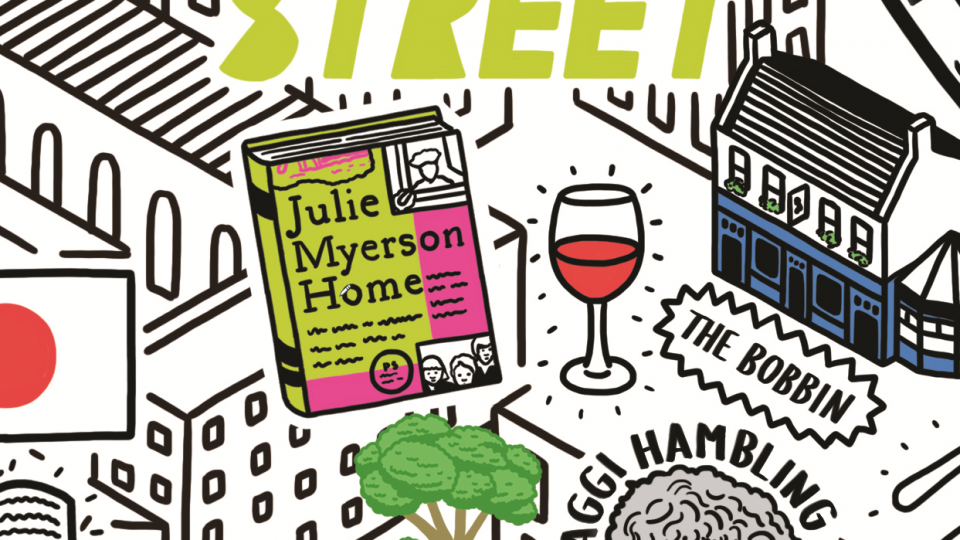

JULIE MYERSON – HOME

In Home, the novelist Julie Myerson breaks new ground by writing the story of the Victorian terrace house in Clapham where she and her family have lived since 1988.

The blurb states that it is an “ordinary” house and that “ordinary” people have occupied it since 1872. Yet as another novelist with a passion for genealogy, Anthony Powell, never tired of reminding readers of this newspaper, the more you study ostensibly ordinary individuals, the more extraordinary they seem. As Powell pointed out, genealogical research, when properly conducted – and Myerson is no slouch as a sleuth – has much to teach us about the vicissitudes of life, the vast extent of human oddness.

The author tells us that in “the long, strange journey of this book” she came across “the kind of material most writers can only dream of: a clutch of human stories so touching, pungent and outlandish that, had I invented them, I might have worried they were too far-fetched and flung them speedily back”. In her admirable determination to bring the story alive she occasionally allows her novelistic imagination to run away with her, so that some of the attempts to flesh out the facts are reminiscent of those awkward “reconstructions” so beloved of television documentary-makers. But she counters these purplish passages with disarmingly down-to-earth interjections from her partner and their three children. “I know the way you write,” her daughter declares. “You’ll put anything in for effect.”

At first, I was not entirely won over by the breezy, chatty style of relating her quest to divine and explore “family, affection, love, generosity, hope, and – however fleetingly – home”, though gradually I became hooked by the adventure. Long before the end I was convinced that Myerson had achieved a work of art. The way she weaves in the experiences of her own itinerant childhood and her difficult relationship with her father (who told her, when she was 16, that he did not want to see her again, and later committed suicide) is masterly and moving.

In true genealogical fashion, the author traces the saga of 34 Lillieshall Road backwards, beginning in the present day. The satisfying result is that this fascinating exercise in social history shows the full circle of social mobility, for back in the 1860s the house was also occupied by an author and journalist. Originally it had been the home of the alcoholic son of Queen Victoria’s Page of the Back Stairs – “my good faithful old Maslin”, as Her Majesty described this stalwart of the Royal Household. In between, we are given intriguing insights into the lives of a remarkable range of people.